Contents

- Preamble

- 1. Bill No. 14062: a framework model of screening and a focus on “classic” security areas

- 1.1 General logic

- 1.2 Areas subject to screening: a narrow list of “sensitive” objects

- 1.3 Screening triggers: control, management, and decisive influence

- 1.4 Procedure and institutional model: centralized administrative decision

- 1.5 Compliance of Bill No. 14062 with the European approach: close, but not identical

- 2. Bill No. 14062-1: factor model of screening and institutional shift towards the AMCU

- 2.1 General logic: from a “list of areas” to risk assessment

- 2.2 Scope: broader, but less formal

- 2.3 Risk factors and screening triggers

- 2.4 Institutional model: the role of the Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine

- 2.5 Compliance of Bill No. 14062-1 with the European approach: closer in logic, more difficult in implementation

- 3. The EU model: how foreign investment screening works in practice

- 3.1 Regulation (EU) 2019/452 as a “superframework”: coordination, not a single permitting authority

- 3.2 Institutional architecture: the role of the European Commission and national authorities

- 3.3 “Sensitive” areas in the EU’s focus: not a list of sectors, but a risk matrix

- 3.4 Typology of decisions: allow, allow with conditions, prohibit

- 3.5 Practical conclusion for Ukraine as a candidate country

- 4. The US Model: CFIUS as a Centralized but Factor-Oriented Mechanism

- 4.1 Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS): Origins and General Logic

- 4.2 Scope: from corporate control to access to technology and data

- 4.3 Risk factors: focus on the investor, technology, and geopolitics

- 4.4 The CFIUS procedure and the nature of decisions: centralization, responsibility, and political backstop

- 4.5 Meta-conclusion: between the EU and the US — the choice of architecture, not image

- 5. Our vision: what model does Ukraine need and what is likely to be supported by European partners

Preamble

In September 2025, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine registered Bill No. 14062 “On screening of foreign direct investments”, which, for the first time at the legislative level, proposed introducing a special mechanism on foreign investment screening in Ukraine for reasons of national security and public order. Within a month, an alternative Bill, No. 14062-1, appeared, proposing a different institutional and procedural model for such screening.

The emergence of two different legislative approaches to the same issue indicates that the state is finally aware of the need for instruments to control foreign investments in strategic areas. The two approaches offer hope of finding an optimal model that would balance the needs of national security, economic development, and Ukraine’s investment attractiveness.

As of early 2026, both Bills are at the stage of consideration by parliamentary committees. Neither of them has been adopted, nor has the final concept of the future screening regime been determined, nor has the timing of its possible introduction been determined. At the same time, the very appearance of these bills is already affecting the investment landscape, especially in sensitive sectors such as energy, the defense industrial complex, and the production of dual-use goods, including unmanned systems.

The relevance of the topic lies not only in the war and security issues. Ukraine is in the process of adapting its legislation to the law of the European Union, and the control of foreign investments has long become an integral part of European and global practice. The model chosen by Ukraine will depend not only on compliance with European standards but also on the predictability of the rules of the game for foreign investors during the period of post-war reconstruction, which will be manifested in their desire (or vice versa) to participate in it.

The introduction of the foreign direct investment screening mechanism becomes a new systemic element of the regulatory environment for foreign investors in Ukraine and directly affects the conditions for market entry, transaction structuring, and investment decisions within the framework of legal support for foreign business in Ukraine.

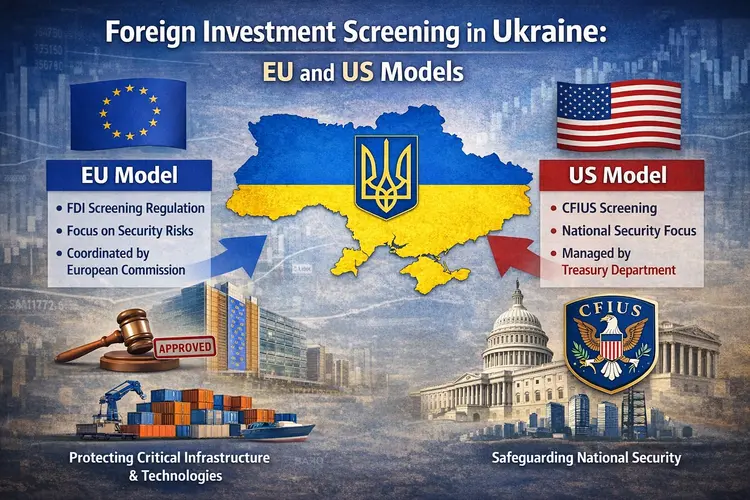

In this article, we compare two Ukrainian Bills on foreign investment screening and examine how they reflect the influence of the European and American screening models. We evaluate the draft laws through the prism of the European Union’s practice (section 3 below) and the CFIUS mechanism in the United States (section 4 below), both of which influenced each draft law. Such a comparative analysis allows us to formulate a model that could be both effective from a security perspective and acceptable to foreign investors in the Ukrainian context.

1. Bill No. 14062: a framework model of screening and a focus on “classic” security areas

1.1. General logic

Bill No. 14062 proposes introducing a special screening mechanism for foreign direct investment (FDI) in Ukraine to protect national security, public order, and the state’s strategic interests.

Conceptually, it is structured as a framework act that defines the basic categories of investments, key screening triggers, and the general powers of government bodies, leaving significant detail for subsequent secondary legislation.

This approach demonstrates the legislator’s desire to quickly lay the foundation for a foreign investment screening without overcomplicating the primary regulatory act. Such a framework seems to be a conscious choice by the legislator in conditions of war and high regulatory uncertainty, when the state seeks to quickly obtain a control tool, even at the cost of postponing complex procedural issues to secondary legislation. At the same time, the political expediency of such an approach does not eliminate its legal consequences – the framework is inevitably transformed into an increased dependence of the investor on future subordinate legislation.

1.2. Areas subject to screening: a narrow list of “sensitive” objects

Bill No. 14062 limits the mandatory screening of foreign investments to three key groups of objects:

- Critical infrastructure operators are included in the relevant state register to be created.

- Use of strategically important minerals, the list of which is approved by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine.

- Activities related to military goods and dual-use goods.

This approach corresponds to the classical understanding of “hard security” and focuses on sectors traditionally considered the most sensitive from a national security perspective. First of all, this is energy, the defense-industrial complex, and strategic resources. Thus, the list of areas actually replaces the individual assessment of transaction risks.

Practical example:

Foreign investments in the production or supply of equipment for power grids (transformers, switchgear, energy storage systems) or in the production of unmanned aerial vehicles and their components will obviously fall within the screening zone, regardless of whether the relevant product is designated as civilian.

This approach reflects the global trend of blurring the line between civilian and military technologies, which is characteristic of both European and American investment screening regimes.

1.3. Screening triggers: control, management, and decisive influence

Screening under Bill No. 14062 is not conducted for any investment, but only if there are signs of control or decisive influence by a foreign investor. Such features include, in particular:

- acquisition of more than 25% of the votes in the supreme management body of a legal entity;

- the right to appoint a sole executive body or a majority of members of a collegial executive body;

- other rights that enable key decisions regarding the enterprise’s activities.

Thus, Bill is focused not on small portfolio investments but on transactions that can actually affect the enterprise’s management and strategic development in a sensitive area. Such a model is convenient from the perspective of legal technique and law enforcement, as it is based on familiar corporate categories of control and management. At the same time, it does not cover situations of actual or technological influence that can arise without formal control. Such a model is also poorly suited to situations of gradual or indirect influence acquisition, which are typical of modern technological and infrastructure investments. Structuring M&A transactions and investments to meet the requirements of the future screening regime is a key element of legal planning.

1.4. Procedure and institutional model: centralized administrative decision

Procedurally, Bill No. 14062 establishes a model in which the key role in screening foreign direct investments is assigned to the central executive body responsible for the formulation and implementation of state investment policy. It is this body that is authorized to make decisions on:

- approval of the investment;

- approval of the investment with conditions;

- refusal to approve.

Given the current institutional architecture, it can be assumed that such a body will be the State Agency of Ukraine for Investment and Development (State Investment Service), whose activities will be coordinated by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine through the First Deputy Prime Minister of Ukraine. Within the framework of the exercise of its powers, the State Investment Service will interact with the Ministry of Economy of Ukraine, which serves as the main body in the system of central executive bodies in the field of investment policy. In addition, the bill provides for the creation of a collegial advisory body under the Ministry of Economy — the Commission for the Assessment of the Impact of Foreign Direct Investments.

The Commission model set out in the bill conceptually resembles the American approach to foreign investment screening implemented by CFIUS, which also serves as an interagency body focused on the security analysis of foreign investments. However, this similarity is more institutional than functional.

In the American model, CFIUS is the only center for risk analysis and the formation of recommendations. In critical cases, the final decision is made at the highest political level — the President of the United States. Thus, the system combines a deep risk analysis with clearly personalized political responsibility for the final decision.

In contrast, the Commission proposed in bill No. 14062 is neither a single analytical center nor a decision-making center. It lacks a defined political level for final decision-making and is not based on a comprehensive, formalized analysis of security risks. The key decision on approval or refusal is made by the State Investment Service, while responsibility for analytical conclusions and recommendations is actually distributed among several executive bodies.

The result is a model that can be conditionally described as a CFIUS image without CFIUS authority, analytical depth, and a political backstop mechanism. Thus, bill No. 14062 attempts to borrow the institutional image of the American model – the interdepartmental Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States – without reproducing its key functional elements: concentration of analytical expertise, clear demarcation of decision-making levels, and personalized political responsibility.

The result is a hybrid structure that is neither a full-fledged CFIUS analogue nor a European cooperative screening model. According to the draft law’s logic, at least five executive bodies may be involved in the FDI screening process, which, in turn, creates the risk of power duplication, blurred responsibility, and fragmented analysis. At the same time, the specific deadlines for procedures, risk assessment standards, and decision-making criteria for each of these bodies remain outside the law.

The key problem with the proposed institutional model lies not in the idea of interdepartmental interaction itself, but in the lack of a clear distinction among the analytical, decision-making, and political responsibility levels. This is what distinguishes the model laid down in Bill No. 14062 from both the American and European approaches to foreign investment screening.

The logic of further foreign investment screening and the idea of creating special investor registers, set out in the draft law, deserve special attention. Such an approach shifts the focus from assessing the risks of a specific transaction to constant administrative supervision of the investor. This is not typical of either European or American practice, where the central object of analysis remains the specific investment transaction and the possibility of mitigating its risks, rather than the “profiling” of the investor. Such a shift potentially increases regulatory risks and reduces the predictability of the foreign investment screening regime for bona fide investors. It is the comparison with the full-fledged American CFIUS model that allows us to see the limitations of this approach, which are discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

1.5. Compliance of Bill No. 14062 with the European approach: close, but not identical

On the one hand, the focus of Bill No. 14062 on critical infrastructure, defense, and strategic resources is well aligned with the logic of the European foreign investment screening regime. These are the “core” areas of security interests in the EU member states as well. At the same time, it is at the level of institutional design and procedural architecture that Bill No. 14062 deviates most from the European model.

On the other hand, Bill No. 14062 pays much less attention to factor risk analysis, proportionality principles, and procedural guarantees for investors. Unlike European practice, where the key is not only “what sector” but also “what risk does a specific investment pose,” the Ukrainian project tends toward a closed list of areas and centralized administrative control. Thus, the proposed model risks recreating an administrative-formal approach to investment control, focused on the procedural and status aspects of the investor, rather than on a substantive assessment of the transaction’s specific security risks.

In conclusion, the model proposed by Bill No. 14062 appears to be an attempt to quickly introduce a foreign investment screening tool by combining elements from different approaches without fully integrating them. This creates the risk that the foreign investment screening regime will work formally, but without sufficient analytical flexibility and procedural trust on the part of investors. The strategic risk of such a model is that it formally performs the function of control but does not build trust, and without trust, the FDI screening regime becomes a factor deterring investment even in sectors where security risks can be effectively mitigated.

2. Bill No. 14062-1: factor model of screening and institutional shift towards the AMCU

2.1. General logic: from a “list of areas” to risk assessment

Bill No. 14062-1 proposes an alternative concept of FDI screening that differs significantly from the framework model in Bill No. 14062. Its key idea is not so much to fix a limited list of “sensitive” sectors, but to introduce a risk-oriented, factorial approach to foreign investment screening.

Instead of proceeding solely from the formal belonging of the investment object to a certain category, Bill No. 14062-1 focuses on analyzing what risks to national security, public order, or economic and infrastructural stability a specific investment may pose, taking into account the characteristics of the investor, the investment object, and the structure of the transaction.

This approach is conceptually closer to modern international standards for FDI screening, where the key is not the presence of foreign capital itself but the potential impact of the investment on the state’s critical interests.

2.2. Scope: broader, but less formal

Unlike Bill No. 14062, the alternative bill is not limited to three strictly defined categories of objects. Foreign investment screening under Bill No. 14062-1 can be applied to a much wider range of investments if they:

- relate to critical infrastructure or its elements;

- provide access to critical technologies, including military or dual-use goods;

- create control or significant influence in areas important for the security and stability of the state;

- relate to access to sensitive data or key supply chains.

Thus, the scope of Bill No. 14062-1 is potentially broader than that of draft law No. 14062, but at the same time, less formalized and more dependent on assessments of specific circumstances. This increases the mechanism’s flexibility but also increases the discretion of the screening authority.

Practical example:

Investments in the production of unmanned systems, their components, software, or sensor technologies may be subject to screening even in the absence of a formal military status for the product, if such investments create access to critical technologies or the possibility of their use for military purposes.

2.3. Risk factors and screening triggers

Bill No. 14062-1 focuses on a set of risk factors to be considered when deciding on the need and outcomes of FDI screening. Among such factors, in particular:

- the nature and structure of the foreign investor (including the presence of state influence or ties with governments of third countries);

- the possibility of gaining control or significant influence over the activities of the investment object;

- access to critical technologies, information, or infrastructure;

- geopolitical and sanctions context;

- the possibility of using the results of the investment for military or other sensitive purposes.

Unlike Bill No. 14062, where formalized control thresholds (25% of votes, managerial powers, etc.) play a key role, in Bill No. 14062-1, qualitative risk analysis becomes the central element of the screening mechanism.

2.4. Institutional model: the role of the Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine

The most controversial element of Bill No. 14062-1 is the proposed transfer of key powers for foreign investment screening to the Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine (AMCU). It is proposed that the AMCU be given the powers to:

- conduct an assessment of foreign investments for reasons of national security and public order;

- make decisions on investment approval, approval with conditions, or prohibition;

- monitor compliance with the conditions imposed within the screening framework.

At first glance, such a decision may seem atypical, especially given European practice, where competition policy authorities usually do not act as FDI screening authorities. At the same time, the institutional logic of Bill No. 14062-1 becomes clearer when viewed through the prism of the evolution of the American model of foreign investment screening.

The American approach to foreign investment screening, implemented through the CFIUS mechanism, has significantly deviated from traditional merger and acquisition controls over the past two decades. Starting with FINSA (2007) and especially after the adoption of FIRRMA (2018), CFIUS’s focus has shifted from the formal acquisition of control over a company to a broader assessment of the economic, technological, and infrastructural impact of the investment. This includes, in particular, access to critical technologies, supply chains, sensitive data, as well as the investor’s ability to form long-term structural dependence in strategic sectors.

It is in this logic that the choice of the AMCU as the screening authority in Bill No. 14062-1 ceases to seem accidental. The AMCU has unique expertise in the Ukrainian institutional system for analyzing complex economic transactions, concentrations, market structure, and their impact on the competitive environment. Its procedural culture, based on factor analysis, assessment of market power, and long-term effects, methodologically approaches the analytical logic that underlies the modern CFIUS.

Thus, the institutional solution of Bill No. 14062-1 can be seen as an attempt to adapt the evolved American risk-based approach to Ukrainian realities by using a body capable of conducting comprehensive economic and structural analysis, rather than just a formal review of “sensitive” sectors.

At the same time, such an adaptation is not without significant risks. The key problem is that, unlike CFIUS, the AMC is a classic regulator with quasi-judicial powers that issues binding decisions in competition law and applies sanctions. Competitive control and foreign investment screening for national security reasons have different legal natures, goals, and assessment standards: the first is focused on protecting competition and consumers, the second on managing risks to security and public order.

Combining these functions in one body creates a risk of mixing approaches, when security analysis can be subconsciously replaced by the logic of competitive effects or, conversely, competitive procedures by arguments of national security.

In addition, unlike the American model, where CFIUS is an analytical center that works in conjunction with a clearly personified political level in the final decision, Bill No. 14062-1 does not provide such a clear “political backstop”, which is critically important for the legitimacy of decisions in the security sphere.

Thus, the proposed role of the AMCU in the foreign investment screening mechanism reflects the logic of the modern American model in terms of the analysis’s content, but is implemented through an institutional instrument more typical of European competition law. This makes the model of Bill No. 14062-1 conceptually attractive but, at the same time, institutionally complex and potentially vulnerable without a clear distinction between the analytical security function, regulatory powers, and the level of political responsibility.

2.5. Compliance of Bill No. 14062-1 with the European approach: closer in logic, more difficult in implementation

From a methodological perspective, Bill No. 14062-1 is much closer to the European model of foreign investment screening than Bill No. 14062. Its focus on risk factors, the proportionality of intervention, and the possibility of agreeing investments with investment conditions aligns with the approaches used in EU member states.

At the same time, the institutional solution regarding the AMCU’s key role has no direct analogue in European practice. In EU countries, foreign investment screening mechanisms are usually implemented through interdepartmental or governmental structures with a clear division of powers between competition policy authorities and security authorities.

Thus, Bill No. 14062-1 appears conceptually closer to European standards, but it also raises complex issues of institutional design that may affect the effectiveness and legitimacy of the future screening regime.

3. The EU model: how foreign investment screening works in practice

3.1. Regulation (EU) 2019/452 as a “superframework”: coordination, not a single permitting authority

The European model of foreign investment screening is based on Regulation (EU) 2019/452, which does not create a single supranational authority with the power to authorize or prohibit investments. Instead, the Regulation establishes a cooperative framework in which EU Member States retain their national foreign investment screening mechanisms, while the European Union ensures information exchange and coordination.

The key idea of the Regulation is that an investment may pose risks not only to the recipient country, but also to other Member States or to the Union as a whole. That is why the European model does not centralize decision-making, but builds a procedure for mutual information, comments, and conclusions.

Thus, Regulation (EU) 2019/452 is a “framework” that:

- does not replace national regimes;

- does not unify screening criteria into a rigid and exhaustive list;

- does not create a single “European CFIUS”.

3.2. Institutional architecture: the role of the European Commission and national authorities

At the EU level, the European Commission performs a coordinating and analytical function, but does not take final decisions on the authorisation or prohibition of specific investments. Its powers are as follows:

- to receive information from Member States on investments undergoing screening;

- analysis of the potential impact of the investment on the security or public order of other Member States or the EU as a whole;

- preparation of non-binding but weighty conclusions that are taken into account by Member States.

The final decision — to authorise, to authorise with conditions, or to prohibit an investment — always remains at the national level. At the same time, a Member State that ignores reasoned reservations from the Commission or other States must be prepared to explain its position, which creates a mechanism of political and procedural accountability without formal coercion.

It is this model — coordination without centralisation — that defines the European approach.

3.3. “Sensitive” areas in the EU’s focus: not a list of sectors, but a risk matrix

The European model is not limited to a closed list of sectors. Regulation (EU) 2019/452 offers an indicative matrix of factors that may be relevant in assessing risks, including:

- critical infrastructure (energy, transport, water, communications, financial systems);

- critical technologies (including dual-use technologies, artificial intelligence, semiconductors, unmanned systems);

- critical resources and supply chains;

- access to or control over sensitive data;

- the nature of the investor, in particular the presence of state control, financing or influence from third countries.

Thus, the focus is not only on the formal status of the investor, but also on the potential risk of a specific transaction in a specific context. For manufacturers and suppliers of dual-use equipment, investment screening is closely intertwined with export control and sanctions compliance regimes.

3.4. Typology of decisions: allow, allow with conditions, prohibit

European practice assumes that a complete ban on investment is a last resort. The following are much more often used:

- permission without conditions – if the risks are absent or minimal;

- permission with conditions (mitigation measures) – for example, restrictions on access to certain technologies, data, management functions, requirements for localization or corporate governance;

- prohibition – only in cases where the risks cannot be reduced by other instruments.

The presence of mitigation measures, rather than the binary logic of “allow/prohibit”, is considered one of the key advantages of the European model in terms of investment attractiveness and legal certainty.

3.5. Practical conclusion for Ukraine as a candidate country

For Ukraine, which is in the process of adapting its legislation to the European Union’s law, the European model of foreign investment screening has several fundamental implications.

Regulation (EU) 2019/452 does not impose a single institutional model on Member States and does not require the creation of a specific screening body. Each state retains the freedom to choose the bodies, procedures, and forms of organization of the foreign investment control mechanism. At the same time, the European approach clearly demonstrates that the key is not the body’s name or status, but the quality of its procedural design.

At the heart of the European model are:

- a clearly defined screening procedure;

- transparent and predictable risk assessment criteria;

- the possibility of coordination and exchange of information with other states and the European Commission;

- the application of proportionate measures, including conditions and restrictions, instead of automatic prohibitions.

The second fundamental element is the risk-based nature of the analysis, in which the decisive factor is not the investment’s formal affiliation with a particular sector or the investor’s origin, but the specific impact of the transaction on security, public order, and the state’s critical interests.

From this point of view, if Bill No. 14062, in its current version, is adopted as a basis for dialogue with the EU within the framework of adaptation to the acquis and its application, Ukraine may need to further refine the FDI screening regime. This is not about formal inconsistency with Union law, but about potential recommendations to increase procedural certainty, introduce risk-based criteria, and limit excessive administrative discretion.

In practical terms, this will mean additional time and institutional costs: revising the law itself, refining or rewriting subordinate legislation, and a period of legal uncertainty for investors at the stage of launching the system. That is why the issue of choosing a screening model is important not only from the perspective of security, but also from the perspectives of the effectiveness of the European integration process and investment predictability.

4. The US Model: CFIUS as a Centralized but Factor-Oriented Mechanism

4.1. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS): Origins and General Logic

Understanding the logic of CFIUS is key to assessing why the institutional solutions of Ukrainian Bills appear either incomplete (No. 14062) or conceptually risky (No. 14062-1).

The American model of foreign investment screening differs significantly from the European one in its institutional architecture, yet it also shares key methodological principles with it. CFIUS is an interagency analytical center that accumulates information, forms a security assessment, proposes mitigation measures, and makes recommendations to the political level.

CFIUS is not a classic regulator in the sense of administrative law. It is a coordination mechanism that brings together representatives of key federal agencies (defense, homeland security, trade, energy, intelligence, etc.) and is chaired by the US Department of the Treasury. It is this interagency nature that allows for the combination of economic, security, and technological analysis within a single procedure.

A key difference from the EU model is that CFIUS functions as a single decision-making body rather than a coordination framework for autonomous national bodies.

4.2. Scope: from corporate control to access to technology and data

The American approach to foreign investment screening has evolved from the classic control of corporate acquisitions to a much broader model that covers:

- acquisition of control over US companies;

- non-control investments in companies operating with critical technologies, critical infrastructure, or sensitive personal data;

- real estate transactions, if they pose risks to military or strategic facilities;

- supply chains and access to dual-use or military technologies.

Thus, as in the European model, the functional risk is crucial, not just the transaction’s formal structure.

4.3. Risk factors: focus on the investor, technology, and geopolitics

The American approach to foreign investment screening is not fundamentally a simple choice between permission and prohibition. In most cases, CFIUS reviews transactions through a system of conditions and restrictions, seeking to reduce specific risks rather than blocking transactions as such. This includes, in particular, limiting the investor’s access to certain technologies or data sets, imposing special corporate governance requirements, dividing functions within the group, or even changing the structure of the transaction itself.

A complete ban or forced asset divestment is relatively rare and is usually used when regulators conclude that no mitigating measures can neutralize the identified risks. That is why such decisions are exceptional and are considered a last resort.

A key feature of the American model is that in the most sensitive cases, the final word remains with the US President. This political level of decision-making acts as a kind of “safety valve”: it legitimizes a harsh intervention in investment freedom and, at the same time, clearly defines who is responsible for the consequences of such a step. As a result, the high centralization of power in CFIUS is compensated by personalized political responsibility, strict interagency coordination, and procedural discipline.

If we compare this approach with the European model, the American system appears more rigid and centralized, particularly given its explicit consideration of geopolitical factors. At the same time, there is important common ground between the US and the EU. In both cases, the focus is on assessing real risks, rather than the formal features of the deal; technology, infrastructure, and data remain the key objects of analysis, and conditional and compensatory mechanisms are considered as a priority alternative to direct bans.

4.4. The CFIUS procedure and the nature of decisions: centralization, responsibility, and political backstop

The American model of screening foreign investments through CFIUS is structured as a phased process, allowing the state to gradually increase the intensity of intervention based on the nature and level of identified risks.

In practice, the process usually begins with a notification of the transaction, which can be voluntary or mandatory, depending on the field of activity, the transaction structure, and the participation of foreign capital. Already at this stage, the investor faces a security-based assessment logic that goes far beyond the boundaries of classic corporate or antitrust analysis.

The initial review allows us to weed out transactions that do not pose significant risks to US national security. If potential threats are identified, CFIUS proceeds to an in-depth investigation that analyzes not only the formal parameters of the transaction but also the technological, supply chain, geopolitical, and institutional aspects of the investment.

A key feature of the American model is that it is not reduced to a binary choice of “allow or prohibit”. A significant number of cases end with permission subject to mandatory mitigating measures – restrictions on access to certain technologies or data, requirements for corporate governance, localization of certain functions, or restructuring of the transaction. A ban or forced alienation of assets is considered a last resort when other means cannot eliminate the risks.

It is fundamentally important that in the most sensitive cases, the final decision is made at the level of the US President. It is this political backstop that provides legitimacy to harsh interventions in investment freedom and clearly personalizes responsibility for such decisions. As a result, the centralization of powers in CFIUS is compensated by a high level of interagency coordination, procedural discipline, and political responsibility.

Compared to the European model, the American approach is much more centralized and rigid in its approach to geopolitical factors. At the same time, there is a fundamental commonality between the US and the EU: the risk-oriented nature of analysis, the focus on critical technologies, infrastructure, and data, and the priority of applying conditions and implementing mitigating measures rather than imposing automatic bans.

For Ukraine, the American model has more analytical than applied value. It demonstrates that a centralized screening regime can work only with a clear institutional architecture, a single center of analysis, transparent procedures, and a political level for the final decision. Without these elements, an attempt to recreate a “CFIUS-like” structure risks turning into formal administrative control lacking sufficient analytical depth and investor trust.

4.5. Meta-conclusion: between the EU and the US — the choice of architecture, not image

A comparison of Ukrainian draft laws with the models of the European Union and the US demonstrates that the effectiveness of the foreign investment screening regime is determined not by the name of the body or the borrowing of institutional “images”, but by the holistic architecture of decision-making.

The European model emphasizes procedural coordination, risk-based analysis, and proportionate leverage, while the American CFIUS system combines in-depth factor analysis with clearly personalized political accountability.

Ukrainian draft laws, on the other hand, attempt to combine elements of both approaches, but so far do not fully reproduce either the European procedural logic or the American concentration of powers and responsibilities.

That is why the key issue for Ukraine is not choosing a “European” or “American” model as such, but rather shaping its own screening regime that is both institutionally viable, procedurally predictable, and compatible with commitments within the European integration process.

5. Our vision: what model does Ukraine need and what is likely to be supported by European partners

The introduction of a foreign investment screening regime in Ukraine is inevitable. The question is not whether such a mechanism will be created, but what it will be like – in terms of legal certainty, institutional capacity, and compatibility with the European regulatory model. This will determine whether foreign investment screening becomes a tool for risk management or an additional barrier to investment in the post-war reconstruction period.

When assessing the proposed bills and possible scenarios for their development, it is advisable to proceed from several basic criteria.

First, legal certainty and predictability. An investor must understand when screening is applied, by what criteria the investment is assessed, and what the possible consequences of the authority’s decision are. Unpredictability or lack of transparency in FDI screening decisions can create a basis for investment and commercial disputes, including those with an international element.

Second, the principle of proportionality. Investment restrictions should be applied only to the extent necessary to protect security and public order, with conditions and mitigation measures taking precedence over outright prohibitions.

Third, institutional capacity. The chosen body or model should be able to conduct complex, interdisciplinary analysis — economic, technological, and security-related — without overloading the system or duplicating functions.

Fourth, compatibility with EU law and practice. It is critical for a candidate country that the new regime does not require radical revision in a year or two during the dialogue on adaptation to the EU acquis.

5.1. Possible scenarios

1) Support for Bill No. 14062 as a “narrow security regime”

This option involves introducing screening focused on classic hard security sectors — critical infrastructure, subsoil, military, and dual-use technologies — with centralized administrative control.

Its advantage is the relative ease of launch and the rapid creation of a formal control tool. At the same time, it is this model that is most at risk of encountering further EU recommendations on finalizing procedures, risk-based criteria, and limiting excessive discretion. In practical terms, this means the possibility of a “double reform”: first adopting a framework law, and then substantially revising it.

2) Support for Bill No. 14062-1 as procedurally stronger

Bill No. 14062-1 appears to be much closer to modern international standards in its content: it is based on factor risk analysis, the principles of proportionality and non-discrimination, and provides for the possibility of approving investments subject to conditions.

At the same time, its institutional solution — the concentration of key powers in the AMCU — raises complex issues regarding the separation of competition and security control. Without a clear “political backstop” and procedural safeguards, there is a risk of excessive legalization of security decisions and a decrease in their legitimacy.

3) Combined model: content — as in 14062-1, institutional design — closer to the interdepartmental

From our point of view, the most balanced option is a combination of:

- procedural logic, principles, and risk factors, laid down in Bill No. 14062-1;

- institutional architecture, closer to European and American practice, but without mixing the functions of the competition regulator and the security analysis body.

This involves creating an interdepartmental mechanism with a clear division of roles: analytical, decision-making, and political levels of responsibility. It is this model that most closely corresponds to the logic of Regulation (EU) 2019/452 and, at the same time, allows us to take into account the evolution of the American approach.

Given the European integration context and partners’ expectations, the most likely scenario is a gradual shift from a framework model to a more complex, risk-oriented system in foreign investment screening in Ukraine. However, this path is the most expensive in terms of time and legal certainty.

It would be much more effective from the point of view of implementation to immediately establish a model compatible with European principles, even if this would require more complex work at the stage of preparing the law. European partners are likely to support not a specific body or the institution’s name, but the logic of the procedure: transparency, proportionality, coordination, and the possibility of risk mitigation.

The analysis was carried out by Ganna Tsirat, Doctor of Laws, partner at Jurvneshservice